Crete called, it want’s its chaos back.

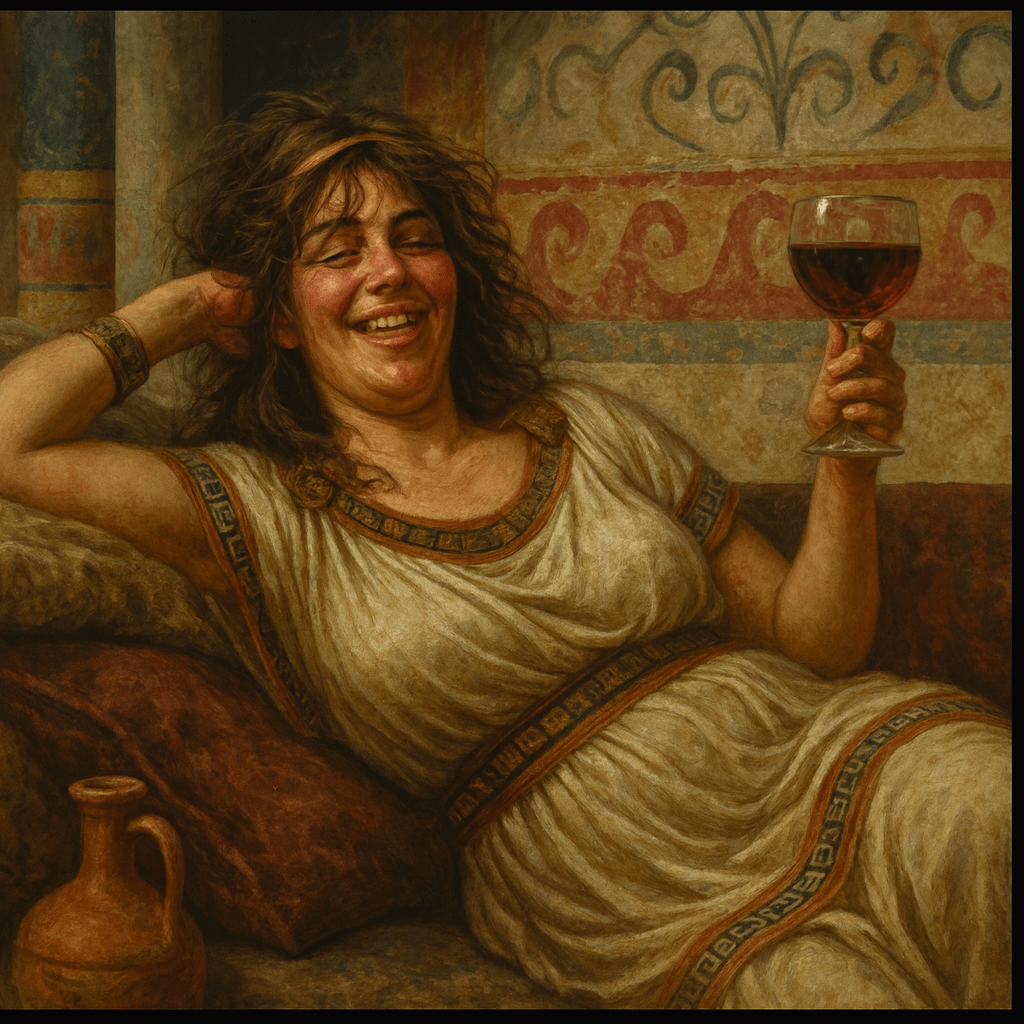

You’ve heard it before — the “older women teaching the younger women” passage that somehow became shorthand for make casseroles and keep quiet.

Funny thing — the Titus 2 list reads an awful lot like the overseer checklist from the chapter before. Same call to be sober, self-controlled, faithful, and above reproach. It’s almost like Paul expected women to meet the same spiritual standards as elders. Imagine that. Turns out, Titus 2 wasn’t a downgrade — it was a promotion. Different arena, similar anointing.

Somewhere between Crete and the modern church, “teaching what is good” turned into “teaching what is palatable.” Mentorship became micromanagement. And a passage meant to strengthen women got rebranded to shrink them.

Before we can reclaim the beauty of Titus 2, we’ve got to remember where it came from — a morally chaotic island, a young pastor trying to stabilize new believers, and a command that called older women to lead with courage, not compliance.

The Passage in Question

“The aged women likewise, that they be in behavior as becomes holiness, not false accusers, not given to much wine, teachers of good things;

That they may teach the young women to be sober, to love their men, to love their children, To be discreet, chaste, keepers at home, good, obedient to their own men, that the word of Elohiym be not blasphemed.”

— Titus 2:3–5, Cepher

On paper, it sounds simple enough — a quick checklist for “godly womanhood.” Be holy, stay sober, love your people, and keep your house in order.

But here’s that pesky little context once again, because when we read this story, these were’t folks sitting on couches in a suburban household bible study.

Paul was writing to Titus, a young leader on the island of Crete — a place the ancient world considered morally unhinged.

In that environment, the goal wasn’t to make women quiet — it was to make believers credible. The early assemblies were being accused of lawlessness, rebellion, and social disorder.

This wasn’t “stay home and behave.”

It was, “Live in a way that silences the slander.”

“…That They May Teach the Young Women to Be Sober”

“That they may teach the young women to be sober, to love their men, to love their children…”

— Titus 2:4

This is usually where someone jumps in with:

“See? Women are only supposed to teach other women.”

Right — and I guess by that logic, women should also only learn from other women. Doesn’t that sound silly?

If we actually step back, Paul wasn’t laying down a universal teaching restriction; he was giving Titus a strategy for spiritual stability in Crete — a culture famous for being, in Paul’s own words, “liars, evil beasts, and lazy gluttons.” (Titus 1:12)

The goal wasn’t to keep women in their lane; it was to keep the gospel credible in a society that thought believers had lost their minds. So Paul’s instruction starts at the most visible and influential sphere of daily life — the home. Because that’s where faith was on display.

Older women were called to lead the charge by modeling maturity in the midst of chaos — to teach what is good (Greek: kalodidaskalos) so the younger women could learn how to live faithfully in a world that had forgotten what faithfulness looked like. It wasn’t about limitation. It was about leverage.

Now, when Paul says “teach them to be sober,” the phrase sounds quaint in English, but the Greek word sōphronizō (σωφρονίζω) runs much deeper.

It comes from sōphrōn, meaning sound-minded, self-controlled, and sensible.

It doesn’t mean “be quiet” or “be subdued.”

It means be in tune.

Think of it musically: a life without discipline is like an instrument out of tune — all potential, no harmony. Sōphronizō is about calibration — tightening the strings just enough to bring the right pitch.

Paul wasn’t telling women to lower their volume; he was teaching them to find their key.

In Crete’s culture of indulgence, gossip, and self-promotion, he called them to become conductors of composure — to live with a steady rhythm that others could follow back to the melody of righteousness.

“…To Love Their Husbands and Children”

“…to love their men, to love their children…”

— Titus 2:4

The next command flows right out of sōphronizō — once the heart is tuned, it can make harmony.

The Greek words philandros (to love one’s husband) and philoteknos (to love one’s children) both stem from philos — the same word for friendship love. It’s warm, devoted, steady — the kind that shows up, not just speaks up.

To love is the command. The universal one.

Men, women, old, young — it’s the fruit of the Spirit, not a gendered chore list.

It’s beautiful, really. And only a silly goose would read it as anything other than the fruit of covenant.

“To Be Discreet and Chaste”

“…to be discreet, chaste, keepers at home…”

Paul adds two words often mistaken for docility: discreet and chaste.

Sōphron (σώφρων) — from the same root as sōphronizō — means balanced and self-controlled.

Hagnos (ἁγνός) means pure — not fragile, but set apart for sacred purpose.

Together, these words paint a picture of strength and focus, not timidity.

A woman who is sōphron and hagnos isn’t quietly fading into the wallpaper — she’s composed, intentional, and unwavering.

So when Paul tells women to be discreet and chaste, he isn’t scripting timidity.

He’s calling them to live with integrity so solid that the noise of the culture can’t throw them out of tune.

…Keepers at Home

“…to be discreet, chaste, keepers at home…”

— Titus 2:5

“Keepers at home” wasn’t about confinement — it was about calling.

The Greek oikourgos (οἰκουργός) combines oikos (household) and ergon (work). It describes diligence, stewardship, and initiative.

If this were about staying put, the Proverbs 31 woman would break the rulebook. She bought land, planted vineyards, ran trade, and strengthened her household’s reputation.

In the first-century world, the home wasn’t a cage — it was a center of influence. Hospitality, trade, worship, teaching — all happened there.

Most early church assemblies met in homes. Lydia, Nympha, and Priscilla all hosted gatherings.

So when Paul said “keepers of home,” he meant guardians of sacred space — women tending the spiritual hearth where community and discipleship were born.

Keeping the home wasn’t confinement.

It was ministry.

Think of it as the stage where the music of faith plays out daily.

A tuned heart (sōphronizō), a melody of love (philandros, philoteknos), and now a steady rhythm of stewardship (oikourgos). Together, they create the kind of harmony that makes the Kingdom audible to the world.

“…Obedient to Their Own Men”

“…to be discreet, chaste, keepers at home, good, obedient to their own men…”

— Titus 2:5

And here’s the line that’s launched a thousand awkward sermons.

The Greek hypotassō (ὑποτάσσω) is usually translated as submission, here they choose obedient, the term in Greek means to align for a shared purpose. It describes partnership — two people walking toward the same mission, each carrying different strengths, both answering to Yahuah.

In the first-century world, Roman law revolved around what were called household codes — social blueprints for keeping order under the paterfamilias (the man of the home). His word was law. He could legally arrange marriages, sell children into slavery, and even end lives within his household.

So when Peter or Paul used words like hypotassō (“align under”) or hypakouō (“listen to”), they weren’t baptizing Roman patriarchy — they were subverting it. They used the familiar language of the empire to teach an entirely different kingdom ethic: one rooted in mutual honor, self-giving love, and unity in Messiah.

That’s why you won’t find this kind of “submission language” in the Tanakh (Original Testament), because they were living in a different cultural moment. Israelite households had structure, sure — but not this Greco-Roman hierarchy of dominance. Torah framed authority through covenant and stewardship, not control.

So when Paul and Peter echo the language of submission, they’re playing chess, not checkers — speaking the empire’s dialect while quietly dismantling its system from within.

In Crete’s culture of chaos, Paul wasn’t saying “fall in line.”

He was saying “walk in step” — so faith wouldn’t be mistaken for disorder.

It’s about shared direction. The beauty of covenant between the husband and wife isn’t control; it’s collaboration.

Titus 2 and Ephesians 5 are singing the same song — different verses, same rhythm. Where one says “submit” and the other says “love,” those aren’t opposites; they’re echoes. And in the Kingdom, we’re all called to both — men and women, to live in in mutual submission and love, modeling the Messiah.

The Real Titus 2 Woman

Maybe the real Titus 2 woman isn’t the one baking in silence or shrinking into someone else’s shadow. Maybe she’s the one building a sanctuary — where truth and grace live side by side, where love is loud, and where peace hums quietly beneath it all.

The world doesn’t need more “quietly compliant” women.

It needs grounded, gracious, spiritually fierce ones — women who know when to speak, when to stand, and when to steady the room with their presence.

That’s what Paul was getting at all along, composing a way of life.

A way that turns chaos into order, noise into meaning, and ordinary homes into outposts of the Kingdom.

So if we strip away the mistranslations and man-made molds, what’s left isn’t a woman contained — it’s a woman commissioned.

A teacher of good things.

A keeper of sacred spaces.

A lover of people and of purpose.

Because the call of Titus 2 has never been to make women small.

It’s to remind the world just how big the gospel can sound when it’s lived through them.

Leave a comment