Some doctrines are born out of deep study. Others, apparently, are born out of sarcasm.

Take Sarah, for instance—the woman who laughed. The one who overheard a divine promise, snorted in disbelief, and muttered something about her “lord” being too old for romance. Yet somehow, that offhand moment of laughter—recorded in Genesis 18—became a proof text for eternal male authority.

Fast forward to 1 Peter 3, and suddenly Sarah’s smirk has been sanctified into a blueprint for marital hierarchy.

You’ve probably heard it before — usually from the kind of guy who wouldn’t mind hearing his wife try it out: “Well, Sarah called Abraham ‘lord.’”

Right. Because nothing says covenant partnership quite like referring to your husband as if he were a minor deity over dinner. Imagine it:

“Would my lord like more potatoes?”

“Of course, my lord, I’ll fetch the remote.”

If that sounds absurd, that’s because it is.

A throwaway line from a private moment in Genesis became a theological badge of male authority — as if Sarah’s sarcastic mutter and bombastic side-eye carried divine weight.

Simple. Neat. And utterly missing the point.

Because when we actually trace Peter’s reference back to where it came from — Genesis 18:12 — we don’t find a woman bowing in solemn reverence. We find a woman laughing in disbelief.

The Laugh That Launched a Doctrine

Let’s rewind to the actual moment Peter is quoting.

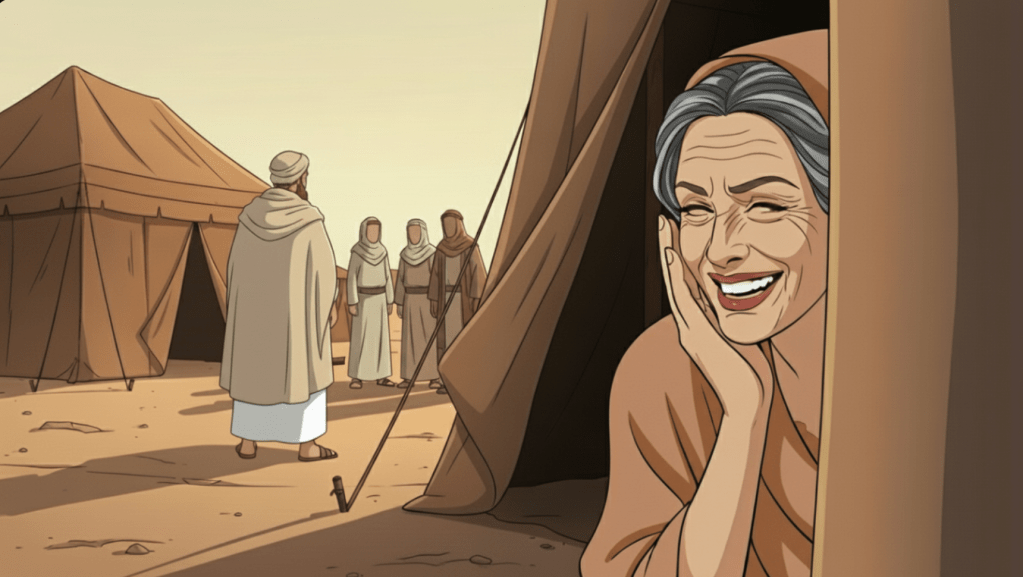

Sarah wasn’t kneeling beside Abraham, whispering titles of devotion. She was eavesdropping behind a tent flap. The messengers had just told Abraham that he and Sarah would have a child in their old age — and Sarah, listening from the shadows, couldn’t help herself.

“Therefore Sarah laughed within herself, saying, After I am waxed old shall I have pleasure, my adoni (lord) being old also?”

— Bere’shiyth (Genesis) 18:12, Cepher

This wasn’t reverence. It was irony.

A tired woman smirking at the thought of rekindled romance with her gray-haired husband — “My lord,” she says, in the same way someone might say, “My husband? At his age?”

It’s half a laugh, half disbelief, and fully human.

Between the time of Hebrew adoni (a term of polite respect) and English Lord (a divine title), the nuance got lost in translation. The smirk became hierarchy. The laugh became law. And somewhere along the line, we forgot she was joking.

The Passage in Question

Now that we’ve revisited the scene — Sarah laughing behind the tent flap, muttering about her “lord” — let’s fast-forward to the moment Peter quoted her.

Here’s the passage that somehow transformed one woman’s sarcastic laugh into a system of marital hierarchy:

“Likewise, wives, be in subjection to your own husbands; that, if any obey not the word, they also may without the word be won by the conduct of the wives; while they behold your chaste conduct coupled with fear.

Whose adorning let it not be that outward adorning of braiding the hair, and of wearing of gold, or of putting on of apparel;

But let it be the hidden man of the heart, in that which is not corruptible, even the ornament of a meek and quiet ruach (spirit), which is in the sight of Elohiym of great price.

For after this manner in the old time the holy women also, who trusted in Elohiym, adorned themselves, being in subjection unto their own husbands:

Even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him adoni (lord): whose daughters ye are, as long as ye do well, and are not afraid with any amazement. Likewise, ye men, dwell with them according to knowledge, giving honor unto the woman, as unto the weaker vessel, and as being heirs together of the grace of life; that your prayers be not hindered.”

— 1 Peter 3:1–7, Cepher

Now, to Peter’s readers — who grew up on the Torah stories — this reference would’ve landed instantly. They knew Sarah laughed. They knew she wasn’t kneeling in reverence but snickering at the absurdity of bearing children at ninety.

But fast-forward two thousand years, toss in a few language shifts, and suddenly “my adoni” becomes “Lordship,” “subjection” becomes “domination” and the whole thing starts to sound like a marriage seminar instead of a faith story.

It’s a perfect storm of lost context: Hebrew nuance, Greek translation, and English piety — all layered together until sarcasm reads like submission.

And yes, I can already hear the objection:

“Why are you even bothering with the Hebrew? This passage was written in Greek.”

Because one — it’s quoting from a Hebrew passage, so duh.

And two — Peter was talking to Hebrews.

The Hebraic mindset is the lens they were reading through. Their Scriptures, their idioms, their worldview — all rooted in Torah. To miss how they read is to miss what he meant.

As Paul reminds us, the New Testament was written for those who already understood the Torah (Romans 7:1, 15:4). It wasn’t replacing the foundation; it was written to those who already stood on it.

So before we start parsing Greek verbs, let’s do what Peter expected his readers to do: read through the lens of Torah, not through the lens of English tradition.

Did Sarah Call Abraham Her God?

Let’s settle this once and for all: no, Sarah was not attributing godship to Abraham.

And before you say, “Well, no one’s actually making that claim,” may I just suggest — spend five minutes on TikTok and prepare to be amazed. Mmmkay?

When Sarah called Abraham “adoni,” she wasn’t granting him divine status. The Hebrew adoni simply means “my master,” “sir,” or “one worthy of respect.” It’s a polite, relational title — the same one used hundreds of times in Scripture for ordinary people. Servants call their employers adoni. Citizens use it for kings. Even strangers use it as a courtesy.

When the Hebrew Scriptures want to refer to Yahuah (The Lord), they use Adonai (אֲדֹנָי) — same root, different form, reserved exclusively for the divine. Sarah didn’t use that word.

So no, she wasn’t calling Abraham her god. She was using the common expression of respect in her language — more like “my husband” or “my good sir” in tone, not “my Lord and my God.”

Peter wasn’t elevating Abraham to deity status; he was quoting a cultural idiom that his Hebrew readers would immediately recognize.

The tragedy is that later readers, distanced by translation and culture, mistook a sarcastic “my adoni” for theological worship.

What Peter Was Actually Doing

Before we crown Abraham the eternal head of household, let’s talk about what Peter was actually writing — and to whom.

Peter’s letter wasn’t a marriage manual. It was a survival guide. He was writing to scattered believers under Roman rule — people already viewed with suspicion for refusing to worship Caesar or the local gods. In that world, a wife who followed another deity wasn’t just disobedient; she was socially dangerous.

So when Peter says, “Wives, be in subjection to your own husbands” (1 Peter 3:1), he isn’t handing down a divine chain of command. He’s giving a strategy for witness. The same rhythm runs through the whole letter: citizens to rulers, servants to masters, wives to unbelieving husbands — all under one theme: live honorably so the world sees Yahusha through your conduct.

The Greek word for subjection is hypotassō (ὑποτάσσω), literally “to arrange oneself under.” It was a word of cooperation, not coercion — of formation, not inferiority. In military use, it meant standing in purposeful alignment; in civil life, it meant choosing peace over pointless resistance.

The same word appears in calls for mutual submission among believers (Ephesians 5:21) and in describing Yahusha’s (Jesus’) willing posture toward the Father (1 Corinthians 15:28). None of these imply weakness — they reveal strength under restraint, power that serves instead of dominates.

Peter wasn’t telling women to lose their voice. He was showing them how to wield it differently.

The Trinity Paradox

And if hypotassō were really about hierarchy, the whole theology would collapse on itself.

Yahusha’s (Jesus’) “subjection” to Yahuah (The Lord) wasn’t a power imbalance — it was unity in motion. The Son doesn’t serve a superior deity; He reveals the Father. They are two dimensions of the same Being, operating in perfect oneness.

So if “subjection” means inequality, we’d have to believe Yahuah somehow outranks Himself. Which makes no sense at all.

Peter is describing the same divine pattern Yahusha modeled — oneness expressed through humility.

The Power of “Likewise”

There’s a small word that quietly stitches Peter’s whole argument together: “Likewise.”

It shows up twice — first at the start of 1 Peter 3:1 (“Likewise, wives…”) and again in 3:7 (“Likewise, husbands…”). That repetition is no accident. It’s Peter’s way of saying, “In the same manner I’ve just described.”

And what had he just described? The suffering of Yahusha.

In the previous verses, Peter wrote about the Messiah who, when insulted, did not insult back; who submitted to injustice without surrendering righteousness; who overcame evil by doing good. Then he turns and says, “Likewise, wives…” — not “likewise, under your husband’s rule,” but “likewise, in the same spirit as Messiah.”

That one word links the whole passage to the cross, not to cultural hierarchy.

But Peter doesn’t stop there. When he says, “Likewise, husbands…” in verse 7, he’s tying men to the very same example. The husband isn’t elevated; he’s enlisted in the same call to humility.

“Likewise, you husbands, dwell with them according to knowledge, giving honor unto the wife, as unto the weaker vessel, and as being heirs together of the grace of life; that your prayers be not hindered.”

— 1 Peter 3:7, Cepher

That phrase, “dwell with them according to knowledge,” isn’t about domination — it’s about understanding. Peter calls husbands to treat their wives as co-heirs of grace, to honor them, and to recognize that spiritual pride cuts off their own communion with Yahuah.

In other words, Peter’s saying, “You both answer to the same standard — the humility of Messiah.”

“Likewise” levels the field, rooted in the example of our Messiah, it’s echoing the call in Ephesians 5 where mutual submission turns the key, and sacrificial love opens the door– It doesn’t crown anyone; it calls everyone to the same pattern of courageous humility.

“Sarah Obeyed Abraham” — Or Did She?

Now comes the part that really seals the argument for most people:

“Even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him adoni (lord): whose daughters ye are, as long as ye do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.”

— 1 Peter 3:6, Cepher

There it is — “Sarah obeyed Abraham.”

The Greek word translated “obeyed” is hypakouō (ὑπακούω), which literally means “to listen attentively” or “to heed.” It carries the sense of hearing — not being under authority, but responding to what is heard. It’s the same root used when Yahuah “hears” prayer or when a person attends to a call.

This isn’t robotic obedience; it’s relational attentiveness. Sarah didn’t blindly obey Abraham — she listened, discerned, and responded within covenant partnership. And let’s be honest, if we actually read Genesis, she had no issue voicing her opinion. She’s the one who told Abraham to send Hagar away — and Yahuah Himself told Abraham to listen to Sarah (Genesis 21:12).

So, if anyone’s “obeying” here, it’s mutual.

Peter isn’t canonizing hierarchy; he’s highlighting character — faith expressed through courage. That’s why he finishes the verse with the line, “whose daughters you are, as long as you do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.”

Not Afraid with Any Amazement

Peter ends his thought with a phrase most people skim past:

“Whose daughters you are, as long as you do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.”

— 1 Peter 3:6, Cepher

If you read that in English, it sounds poetic — or maybe just vague. But in Greek, the phrase “not afraid with any amazement” (μὴ φοβούμεναι μηδεμίαν πτόησιν) paints a vivid picture. It literally means not being shaken, startled, or thrown into panic.

Peter is commending women for their fearlessness, not their fragility. He’s saying, You’re Sarah’s daughters when you do what is right and refuse to be intimidated.

And here’s where we need to connect the dots: Sarah’s strength wasn’t in bowing to Abraham; it was in trusting Yahuah’s plan through Abraham. She wasn’t surrendering to her husband’s whims — she was aligning herself with the covenant Yah had spoken over them both.

When Peter says, “do well and do not fear,” he’s echoing that same pattern. Sarah didn’t do good because she was told to — she did good because she believed. She trusted that Yahuah’s word was worth following, even when it came through her husband. That’s not blind obedience; that’s spiritual discernment.

Her “subjection” was about cooperation with Yah’s will, not compliance with man’s control.

And that’s the difference Peter is driving home. The women he’s writing to were being called to the same thing — to stand firm, do good, and refuse fear. To live in such strength that even unbelieving husbands might be “won without a word.”

Sarah didn’t enter the covenant by submission to Abraham’s authority; she partook in it by aligning with Yahuah’s promise. She trusted the voice of the One behind the man — and that’s what made her fearless.

She laughed in disbelief, then believed anyway.

Leave a comment